Written by Andrew Dawes

This article was published in the Architect's Journal on 16 February 2012

The Humanity of Hertzberger

RIBA Gold Medalist Herman Hertzberger has spent the past 50 years designing buildings on a human scale.

The Netherlands is a low-lying country next to the North Sea with a large proportion of its land lying below sea level. Its landscape has been created artificially through centuries of protection and reclamation from the sea, in turn creating a strong collective ethos among its people. The Dutch developed an ability to make the most of little spaces, to produce a communal urban spatiality that reinforces self-recognition and freedom. It is this same spatiality that Herman Hertzberger sets out to recreate in his buildings, providing a framework for the inhabitants and users to express their individuality.

Hertzberger opened his own practice in 1958, when the architects of Team X were starting to question the functionalist Modernist principles of CIAM, which until then had been widely accepted in the Netherlands as the best means of housing a rapidly growing population. Hertzberger edited the journal Forum from 1959-63, together with Aldo van Eyck and Jaap Bakkema (both members of Team X) where they put forward their ideas for a new architecture focusing upon the social interaction that architecture could offer.

The late 60s was a period of protest, with growing disillusionment that the genuine social and cultural change promised by Modernism had failed to materialise, and resistance to large-scale planning and intervention. The enlightened Dutch attitude towards architectural patronage encouraged both commercial clients and bureaucrats to be innovative and appoint barely emerging talents for large commissions. Hertzberger was given the opportunity to put his ideas into practice very early in his career, and his buildings answered the popular cries for human-scale architecture and emphasis on the individual.

In his early works, Hertzberger’s buildings were composed of individual elements reflecting the scale of the user, which were then combined to create zones and spaces for interaction, the whole being articulated as a collection of parts. This was mirrored by the material construction of the buildings; in the expression of the individual building components such as columns, steps and windows, and in the raw materiality of exposed concrete and concrete blocks, all combining to invite inhabitation and interaction.

Centraal Beheer (1972) is perhaps his most well known work from this period. Here, Hertzberger produced a building composed wholly of smaller blocks, reflecting small groups of workers joined together to create teams, departments, which as a whole created a matrix of elements inviting participation and occupation by the inhabitants. On the inside it was a honeycomb of spaces.

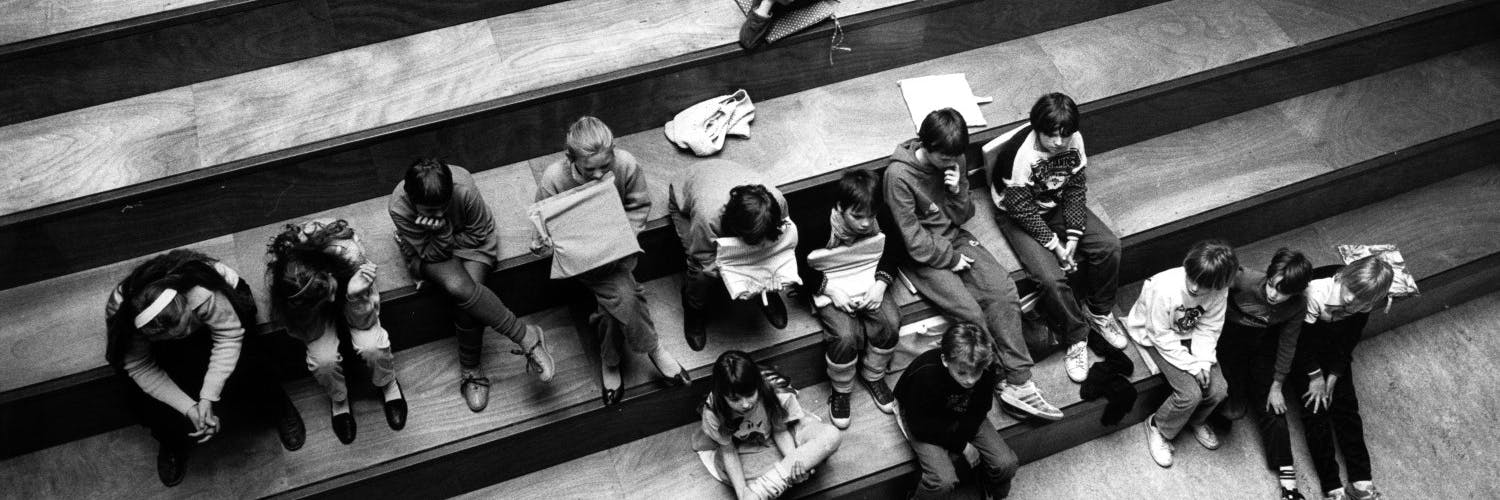

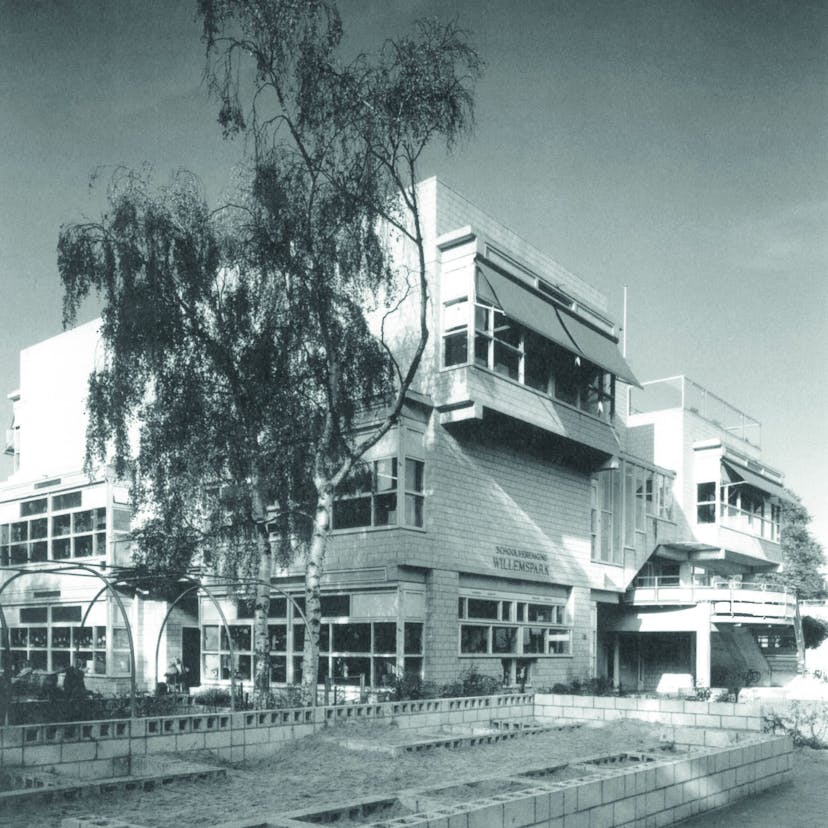

His schools explored the same ideas, and in his Apollo schools in Amsterdam (1983) individual classrooms are grouped around and open on to the heart of the school, inviting engagement from the children and providing a central space for activities. His buildings from this period, together with his teachings and writings, had an enormous impact upon the architectural thinking of the time.

But by the 1980s the Structuralist approach of Hertzberger was beginning to be seen as over-complicated, and the Brutalist materiality of his buildings had not aged well. Form in architecture had moved back into the spotlight, with an influx of renowned foreign architects winning public commissions and Rem Koolhaas proposing radical new building typologies and offering flashy commercialism and cheap materials.

Koolhaas’ writings and the work of his practice were to give birth to a new generation of young practices, sharing a high level of conceptual and typological inventiveness and responding to the new global economic and political developments offered by the internet and a unified Europe. However, their buildings also shared a strong sense of communality and shared values, in part bred from the Dutch collective ethos, but perhaps also as testimony to the influence of Van Eyck and Hertzberger through both their teachings and work.

Apollo Schools, Amsterdam

In his early works, Hertzberger’s buildings were composed of individual elements reflecting the scale of the user, which were then combined to create zones and spaces for interaction, the whole being articulated as a collection of parts. This was mirrored by the material construction of the buildings; in the expression of the individual building components such as columns, steps and windows, and in the raw materiality of exposed concrete and concrete blocks, all combining to invite inhabitation and interaction.

Centraal Beheer (1972) is perhaps his most well known work from this period. Here, Hertzberger produced a building composed wholly of smaller blocks, reflecting small groups of workers joined together to create teams, departments, which as a whole created a matrix of elements inviting participation and occupation by the inhabitants. On the inside it was a honeycomb of spaces. His schools explored the same ideas, and in his Apollo schools in Amsterdam (1983) individual classrooms are grouped around and open on to the heart of the school, inviting engagement from the children and providing a central space for activities. His buildings from this period, together with his teachings and writings, had an enormous impact upon the architectural thinking of the time.

But by the 1980s the Structuralist approach of Hertzberger was beginning to be seen as over-complicated, and the Brutalist materiality of his buildings had not aged well. Form in architecture had moved back into the spotlight, with an influx of renowned foreign architects winning public commissions and Rem Koolhaas proposing radical new building typologies and offering flashy commercialism and cheap materials. Koolhaas’ writings and the work of his practice were to give birth to a new generation of young practices, sharing a high level of conceptual and typological inventiveness and responding to the new global economic and political developments offered by the internet and a unified Europe. However, their buildings also shared a strong sense of communality and shared values, in part bred from the Dutch collective ethos, but perhaps also as testimony to the influence of Van Eyck and Hertzberger through both their teachings and work.

Chasse Theatre, Breda

The response of Hertzberger was to reinvent his architectural language without compromising his social goals. His buildings employed a stronger collective framework to define the project at the larger scale, which in turn housed the individual elements in a more fluid form. The Chassé Theatre in Breda (1995) employs a huge undulating roof to house the foyer and auditoria, which becomes the main facade of the building to the city. The courtyard housing in Düren (1996) uses a roof and plinth as collective elements to provide shelter and space, while housing a plethora of volumes and typologies at the scale of the dwelling between, forging these different elements into a single urban entity. In both examples, it is the collective component (the gesture) that defines the form and provides the framework for the individual elements. This was reflected in the architectural grammar, as the individual components of the buildings became less expressive, while cleaner, more modern materials replaced the raw brutalism of his earlier works. It is often only close up or within the buildings that the richness of structural ingenuity and articulation is revealed.

If Hertzberger’s work was originally influenced by the members of Team X and fellow editors of the journal Forum, it was perhaps his co-founding and deanship of the Berlage Institute in Amsterdam that influenced his later work and enabled him to stay at the forefront of architectural thinking over a career spanning more than 50 years. The school provided Hertzberger with the opportunity to invite architects from across the world to participate and engage in architectural debate. While Hertzberger’s early work rigidly linked thought and form, his later work has flourished in its free-flowing language without changing the criteria of its approach.